I was recently invited to give a talk for the New South Wales Dickens Society. I had no hesitation accepting, not as an aficionado of Dickens literary works, but because Charles Dickens’s wife Catherine (nee Hogarth), published a book of menus in the 1850s.

Revised in 1854, the book had several print runs, and was listed for sale in Australia by 1855, presumably helping to shape tastes on colonial tables.

Enter Lady Clutterbuck

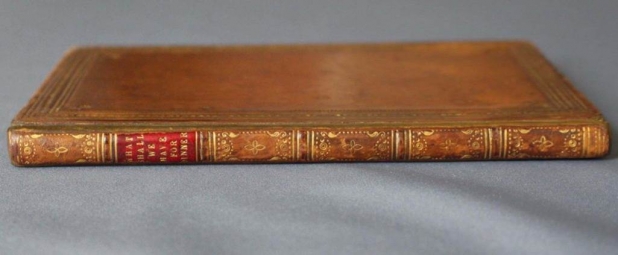

‘What shall we have for dinner?‘ was published under a pseudonym, ‘Lady Maria Clutterbuck’ (something of a private joke, Lady Clutterbuck had been a character in the Dickens farce ‘Used Up’). The title’s question was ‘satisfactorily answered by numerous bills of fare for from two to eighteen persons’.

A diminutive but handsome volume of menu suggestions, the book gives us a fascinating glimpse into the tastes in Dickens’s time, and possibly, the types of foods enjoyed at the Dickens’ family table.

‘What shall we have for dinner?‘ by Lady Maria Clutterbuck, 1852. Photo © The Dickens Museum, London.

In good company

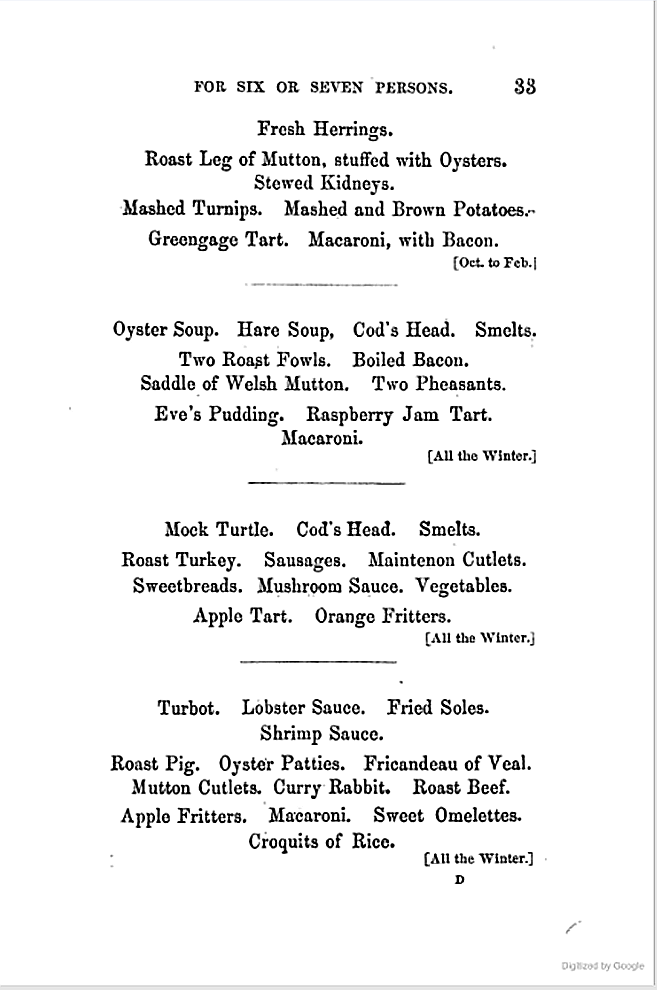

What shall we have for dinner? joined a plethora of domestic management and household advice manuals, hungry for a share in market created by the burgeoning middling class in the 19th century. The book’s principal focus is on menu planning, but it also includes a selection of recipes which the author claimed were commonly ‘misunderstood’. They range from simple Cock a Leekie, to salmon curry (made with curry powder and curry paste), a sweet hominy and Kidney’s a la brochette.

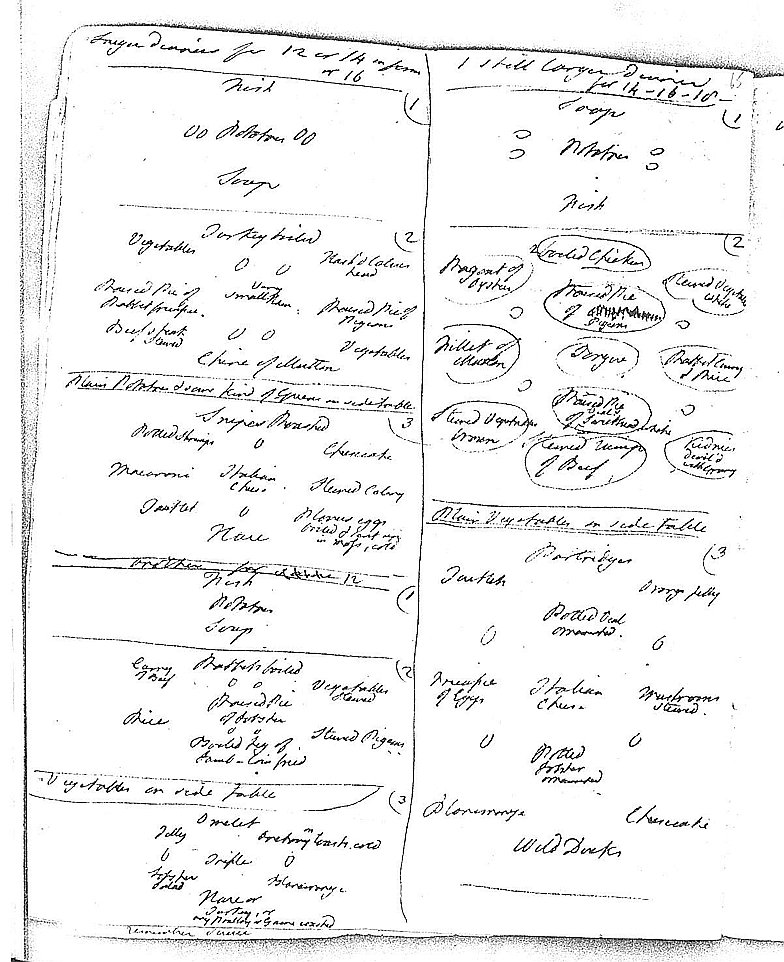

Sample page from What shall we have for dinner? by Lady Clutterbuck, 1852. Accessed via Google Books.

Echoes of the past?

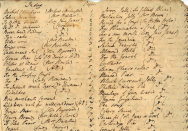

Whether the book was Catherine’s idea, her husband’s or his publisher’s, who no doubt profited from its success, regular readers of this blog will recognise that this was not an original idea. Thanks to a benevolent aunt, Anna-Maria Macarthur was equipped with a repertoire of 70 menus and hints on how to entertain when she entered colonial society, in 1813, as Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur’s bride.

Copy of page from Household hints, compiled for Anna Maria Macarthur, ca. 1813, with notes by Rachel Roxburgh, 1967. State Library of NSW MLMSS 1428

‘X’ marks the spot

While it is fascinating to see the types of dishes deemed suitable for family and sociable dining, the layout of the menus is of particular interest; written on the page according to the way the table should be set, as a form of ‘mud map’. The style of dining in both Catherine’s and Anna Maria’s menus is ‘a la Francaise‘ which we have written about on this blog in the past – here, here, and here for example.

Democratising the art of the table

What shall we have for dinner?, and other published works of its ilk, helped democratise previously closeted knowledge about domestic practice, once reserved for the elite. While dining etiquette was a necessary social art, especially for those who had recently acquired a place at fashionable tables, maintaining an appetite for the home was part of the book’s selling point.

Catherine Dickens, nee Hogarth. 1838. Image in Public Domain, via wiki commons

Appetite ‘secured’

The introduction to What can we have for dinner was written by Dickens himself. [1] He assured readers that the Bills of Fare enclosed had met with the approval of Lady Clutterbuck’s equally fictitious late husband, Sir Jonas Clutterbuck. Indeed, Lady Clutterbuck’s ‘attention to the requirements of his appetite secured [said Lady] the possession of his esteem until the last’.

The dreaded Club

This notion is telling of the times – women were often entirely dependent on their husbands and there was a moralistic fear that a man might stray from the home and family in favour of his ‘club’. Dickens cautioned,

‘a surplusage of cold mutton or a redundancy of chops are gradually making the Club more attractive than the Home, rendering ‘business in the city’ a more frequent occurrence than it used to be in the earlier days of their connubial experience.’

Sadly for Catherine Dickens, good food was not enough to keep husband Charles at the family table, and the couple separated after twenty-two years marriage, in 1858.

Daguerreotype of Catherine Dickens taken in 1852 Image source: wiki commons

An elegant sufficiency?

A fifth and final edition of What shall we have for dinner? was published in 1860, two years after the Dickens had formally separated. This suggests that their strained relationship did not prevent Dickens publisher supporting Catherine’s work, so why did it stop there?

My theory is that Catherine’s book, along with many other culinary texts of the time, was cannibalised by the arrival of Isabella Beeton’s Book of Household Management, in 1861.

Carte-de-visite of Mrs Charles Dickens, by J. E. Mayall c1851. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA. Image source: wikicommons

Enter Mrs Beeton

Written with great authority by an ambitious 22 year old, Beeton’s hefty tome dominated the market for generations. Isabella also had connections in the publishing game – namely her husband, Samuel Orchart Beeton. It included 22 Bills of Fare for each calendar month – with menus for dinners of 6, 8, 10, 12 and 18 persons, and two weeks menus suggestions for ‘plain family dinners’. She also gives supper menus for a winter and summer balls for 60.

Isabella Beeton c.1860. Photographer unknown. Image source: wikicommons. Note the similarity of the pose and photography studio setting in the image of Catherine Dickens, above.

With Beeton providing recipes for every dish mentioned, perhaps there seemed little need for Catherine’s humble volume. While the illustrious Charles Dickens has been immortalised with his literary works, What shall we have for dinner? has ensured Catherine a rightful place in culinary history.

Gothic style frontispiece from Beeton’s Book of Household Management. 1861.

Links and further reading

[1] Susan M. Rossi-Wilcox, Dinner for Dickens, Prospect Books, 2005.